We Are Waves Of The Same Sea

Volunteers thank members of a medical assistance team at a ceremony marking their departure after helping with the coronavirus recovery effort, in Wuhan, China, on March 19, 2020. Stringer/AFP via Getty Images

Last week, a large consignment of crates arrived in Italy, addressed to the country’s Civil Protection Department, from the consumer electronics giant, Xiaomi. Inside were tens of thousands of FFP3 face masks for Italy’s healthcare workers, a “token of gratitude to the Italian people” from the Chinese company for making their workers feel so welcome when they opened their first European offices in 2018. Stapled to the side of each of the crates was a quote, in both Italian and English, attributed to the Roman philosopher, Seneca.

“We are waves of the same sea, leaves of the same tree, flowers of the same garden.”

Amidst the panic, the donations keep on coming. At the height of the outbreak in Wuhan the European Union donated 50 tonnes of equipment to China. Two days ago China returned the favour, sending the embattled continent two million surgical masks, 200,000 N95 masks and 50,000 testing kits. In the Phillipines, Manny Pacquiao just donated 600,000 masks to frontline healthworkers. Jack Ma, founder of the world’s largest e-commerce platform, is shipping one million masks and 500,000 testing kits to the United States. That’s on top of the 1.8 million masks and 100,000 test kits he’s already sent to Italy and Spain. Trip.com is delivering a million surgical mask supplies to Japan, Korea, Canada and France, among others. They also put a quote on the sides of their containers, reading “Many ways, to join one journey. Many origins, to reach one destiny. Many friends, to form one family. Many endeavours, to win one victory.”

Masks are a good symbol for this current moment in time. They arrive via planes and container ships, making their way to the frontlines via a global trade network that seemed inevitable, until it wasn’t. For news organisations, they’re convenient symbols of fear and uncertainty. We’ve all seen the images; masked figures hurrying across abandoned streets, or swarming around hospital beds. The stories are accompanied by a blizzard of numbers, figures, casualties and infection rates, which inevitably include some aspect of the national interest. ‘Our’ casualties prioritised over ‘theirs,’ ‘our’ people stranded overseas, ‘here’ being infected by a traveller from ‘there,’ something ‘their’ society does that ‘our’ society would not. This is what the media business knows best. This is the content that dominates our screens.

Alongside the anxiety and narrow-mindedness however, the mask also represents a world all in action at once, waves of the same sea, united against a common threat. When you put on a mask your features disappear, erasing the differences of skin colour or face shape that trigger so many of our socially conditioned responses to the news. The masks work just as well whether you’re black, brown or white, Chinese, Italian, or Nigerian. What we are seeing now is something truly global in scale. In Singapore, gaming company Razer is repurposing its production lines to make masks, in France, luxury cosmetics manufacturer LVMH is now making hand sanitiser, in the United States, General Motors and Tesla are offering to retool to make ventilators and the British government has distributed ventilator blueprints to more than 60 industrial companies, including Rolls-Royce, Airbus, Jaguar and Land Rover.

As writer and historian Rebecca Solnit has documented, in times of real crisis people tend to come together. In New York, a network of thousands of volunteers created by two 20-somethings is delivering groceries and medicine to older residents and other vulnerable people. In the United Kingdom a network of over a thousand mutual aid groups has sprung up overnight, creating platforms for people to help others locally. In Canada, what started as a way to help vulnerable people in metropolitan cities has now become a widespread ‘caremongering’ movement across the country. In China, the hard-hit town of Caohe, near the centre of the coronavirus outbreak, received a gift of tens of thousands of dollars worth of medical equipment from a Taoist nunnery 1,000 kilometres away. The Netherlands and Denmark are already paying their citizens, essentially, a basic income. Other countries will follow. In cities across the world restaurants are closing and being converted to community kitchens so that people who need food can eat.

The point here is not whether humans are good or bad in a crisis — the point is that we should beware of journalists trying to come up with an angle. As Venkatesh Rao points out, we’re dealing with global narrative collapse. Humanity has quite literally, lost the plot. “Narrative collapse events tend to have a very surreal glued-to-screens quality surrounding them. Everybody is tracking the rawest information they have access to, rather than the narrative that most efficiently sustains their reality (…) during narrative collapse, everyone temporarily abandons attempts to reach narrative consensus even within their smallest default groups, such as family. Even people who normally avoid math start to do math with raw, noisy facts. Pantry stocks math. Alcohol percentage math. Infection risk math. Toilet paper math. The average human only goes data-driven when narratives fail.”

Narrative collapse is an uncomfortable place for us to sit in. Here in the West, we’ve been swept up by a convoluted plotline that emerged after the 2008 financial crisis — the loss of faith in elites, the decline of expertise, the rise of populism, increasing polarisation between the left and right. Instead of debating policy, we’ve been arguing over who gets to frame the debate. “The Republican Party has lost its mind,” or “Labour supporters are anti-Semitic,” or “carbon is good for society.” The best example of this is the reality television show that passes for politics in the United States, where any semblance of governing has been replaced by an endless succession of episodes about which side got more owned by the other.

Now though, we’re dealing with a real crisis.

Our elaborately constructed narratives no longer apply. The usual “he-said, she-said” of political debate doesn’t seem as important any more. The electoral horse races, the sports rorts, the outrage over unfair dismissals, the secret affairs, they’re all revealed for what they are: plot devices in a story built to entertain rather than inform. When exposed to harsh reality, narrative tends to collapse under the weight of its own contradictions.

One of the big stories we’ve been entertaining ourselves with for the past few decades for example, is that globalisation is inevitable. We’ve gotten so used to it that it seems like a fact of nature, like air and wind. However, in the process of opening borders to free trade and financial flows we’ve dramatically increased global complexity, added some bite with the geopolitical changeover from a unipolar to a multipolar world, and then poured on rocket fuel with a digital revolution. A globalizing society is, as the German sociologist Ulrich Beck has long argued, a risk society. It’s anti-fragile, meaning that the risk is a feature, not a bug. Something like this was inevitable, and now signals a radical transformation, of the kind that occurs once in a century, shattering previous assumptions. It doesn’t matter if you call it a Black Swan or a Grey Rhino or a known or unknown unknown. The truth is that nobody really saw this one coming: a tiny bundle of protein, 120 nanometres in diameter, carrying just eight kilobytes of genetic code.

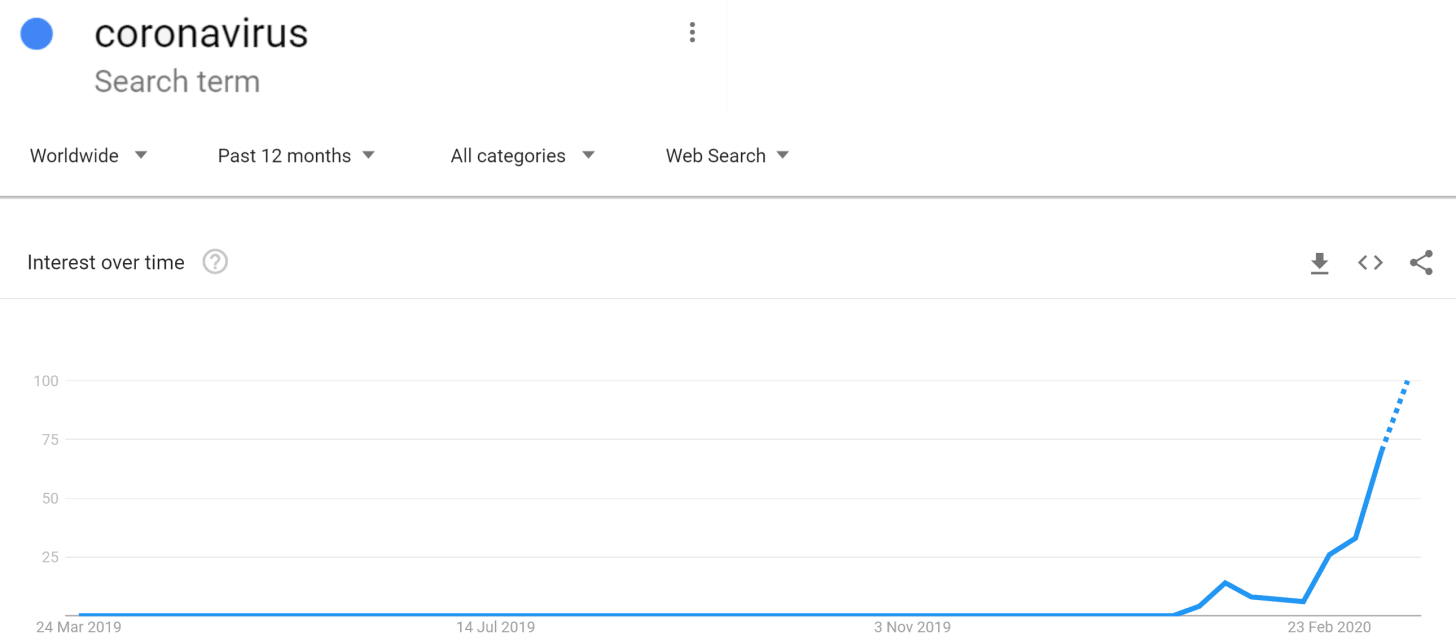

The countries from what might be called the Confucian cosmopolis did have a taste in the form of SARS in 2003 and then MERS in 2012, which is why they’ve dealt with the pandemic so much better than anywhere else. Taiwan has millions of visitors from China a year, and yet has only reported just over 100 cases. Singapore immediately created an app that could physically track everyone who was quarantined, Vietnam has shown a remarkable ability to contain the spread, and South Korea, a democratic republic, created the most expansive and well-organised testing program in the world, combined with extensive efforts to isolate infected people and trace and quarantine their contacts. The rest of the world though, and in particular Europe and the United States, has been shockingly ill-prepared. Political leaders in these places still think we’re living in a linear and predictable system. They’re used to waiting for the signal of a huge systemic shock before they take action, which is why insufficient preparations have been made along the way.

In the immortal words of Upton Sinclair, it’s difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

Many governments, including here in Australia, continue to treat the pandemic as if it’s an external force on the system that we must respond to proportionally. The language of these interventions is reminiscent of a military conflict — this is “a war” against the spread of a virus and economic collapse. As it gets worse, our leaders plan to ramp up defensive measures in response. But coronavirus is not an external force, it is an endogenously generated one, and because we grow this force through our behaviour, the slow ramping up of mitigation guarantees the expenditure of many more resources across a much longer cycle. Intensive care demand lags new infections by about three weeks because it takes that long for a newly infected person to get critically ill. Acting before the crisis hits — as was done in some Chinese cities outside Wuhan, and in some of the small towns in Northern Italy — is essential to prevent a health system overload. If you’ve heard it once, you’ve heard it a thousand times: we need to flatten the curve, and the best way to do that is to overreact.

You should really watch this Kurzgesagt video, it’s one of the best explanations anywhere on the internet.

If you live in a developed country, chances are you’ve never experienced anything like this, and in many (although not all) developing countries the situation is also unprecedented. What’s going to happen? Will our parents be alright, will the hospital system be overwhelmed, what happens if I get sick? Is there going to be an economic downturn, will my favourite restaurant go out of business, how many people are going to die, and when can we start having post-work drinks on Friday evenings again? For many of us, it’s hard to sit in this space of not knowing. We’re used to having answers and so we’re striving for some kind of certainty. We spend hours scrolling through our feeds, trying to find someone who can tell us when it will end, when life will go back to normal and when we can get back to the way things used to be.

Not since the financial crisis of 2008, when there were fewer smartphones in the world by a factor of ten, has the world faced an emergency like this. And while the financial crisis affected countries differently, the coronavirus affects countries in pretty much the same way. The supply chains are slowly breaking, airlines are slashing their flights, country after country is closing its borders and the stock exchanges convulse with fear. The gains of a 12 year bull market have been wiped out in a matter of weeks. Trillions of dollars of infusions into the financial markets haven’t halted the plunge and the central banks are running out of levers to pull. We are living in extraordinary times, and as the weeks stretch into months, we’re going to start realising there is no going back.

There is an upside to all of this. Like someone who has a heart attack and realises their lifestyle might be killing them, we are being forced to take a long hard look at how we’re operating as a global society. Some of the most striking stories to come out of the crisis for example, have been the environmental wins. Dolphins are returning to harbours on the coastlines of Sardinia, in Venice the canals are clearing up, and across Europe the skies are suddenly free of planes. Wet markets have been banned across Asian countries, and air pollution has dropped dramatically. According to some back of the envelope calculations, the reduction in ground-based concentrations of PM2.5 in China has likely saved the lives of 1,400 children under the age of 5 and 50,000 adults over the age of 70. That’s roughly 20 times the number of lives that have been directly lost to the virus in China.

This is not to say COVID-19 is a good thing. These are not the kinds of trade-offs any sane civilisation should be making. The virus is acting as a mirror, forcing us to carefully examine our way of life. Earthquakes destroy much, but they also reveal valuable information about the deepest layers of the earth. Similarly, pandemics cause immense pain and suffering but teach us a great deal. They show us that the industrial economy we’ve always taken for granted is killing us. They force us to sit up and acknowledge that we’re sharing a planet with other species. They reveal who society’s real key workers are. The nurses. The doctors. The delivery drivers. The carers. The porters. The teachers. The shelf stackers. The check out staff.

The virus also shows us that our elected officials are way out of their depth. In a pandemic, narrative doesn’t matter. A crisis like this strips away the bombast and reveals who’s wearing clothes, and who’s standing around naked. Jair Bolsonaro is now insisting he knew it was a crisis all along, but Brazilians won’t forget the months he spent on national television claiming it was a hoax. In the United States, the current occupant of the White House is furiously trying to re-brand himself as a wartime president, but viruses pay no heed to names and titles. It doesn’t matter how many dead Chinese Virus cats you throw on the table. Testing shortages are testing shortages, there’s only so many hospital beds to go around and if you spend three years systematically stripping your civil service of anyone who refuses to pledge loyalty, the country that elected you is going to pay a heavy price.

On a broader level, with each passing day we see more clearly that our antiquated, hidebound, unloved governments are no longer up to the job of coping with the kinds of challenges that face us in the 21st century. Global pandemics, climate change, cyberwarfare, biological warfare, ecosystem collapse — these are threats that require younger leaders with better ideas, safety nets and protection for working people in societies with rising inequality, national health-care systems that cover the entire population; public schools that train students to think both deeply and flexibly; and much more.

For me though, the most encouraging thing to emerge from this pandemic is that we’re finally starting to take scientists seriously again. For the past decade, populists have hammered the experts who contradict their public claims and interests. But those experts, whose budgets and capabilities have so often been eroded by the leaders who despise them, are now our main line of defence. Isn’t it interesting that when the going gets tough, scientists are suddenly back in vogue? New York Times journalist Farhard Mahoo says it better than we ever could:

Let us pray, now, for science. Pray for empiricism and for epidemiology and for vaccines. Pray for peer review and controlled double-blinds. For flu shots, and washing your hands. Pray for reason, rigour and expertise. Pray for the precautionary principle. Pray for the NIH and the CDC. Pray for the WHO. And pray not just for science, but for scientists, too, as well as their colleagues in the application of science — the tireless health care workers, the whistle-blowing first responders, the rumpled, righteous public servants whose long-ignored warnings we will learn about only when the 12-part coronavirus docu-disaster series drops on Netflix. Wish them all well in the fights ahead. Their weapons, the weapons of science, are all we have left — perhaps the only true weapons our kind has ever marshalled against encroaching oblivion.

Don’t forget the scientists. There are more of them alive today than have ever existed, and right now as you’re reading this, they’re all pulling in the same direction. Medical research is faster and of higher quality than at any other time in history. It only took two weeks after Chinese health officials reported the virus to the World Health Organisation for geneticists to isolate it and publish the full sequence. During the SARS outbreak in 2002 it was months before the viral genome was sequenced and longer still before it was remade in the lab. Back then, it cost $10 to create a synthetic copy of one single nucleotide, the building block of genetic material. Now, it’s under 10 cents.

Dozens of biotech companies and public labs around the world have created those synthetic copies, and are working around the clock. In the last 72 hours, three companies that specialise in messenger RNA therapeutics, BioNTech, CureVac and Moderna, have announced they have candidates. Animal testing has shown promise, and human trials are now just weeks away, with a vaccine expected to be ready for public use within the next 12 to 18 months. That means that a vaccine could become available within two years of the virus’s emergence. By comparison, it took 48 years to create a successful vaccine for the polio virus, and decades for most other vaccines, including Ebola.

It was scientists who discovered the threat, sequenced the genome, and built the internet protocols that now allow information about the virus to travel faster than the virus itself. When bad science happened, as it did with the herd immunity strategy in the United Kingdom, it got called out by other scientists, and changed course. Thanks to science, we already have a number of potential treatments under evaluation, such as the flu drug favipiravir, repurposed HIV-fighting drugs, such as lopinavir and ritonavir, and chloroquine phosphate, which is normally used to treat malaria and liver infections.

Most importantly, science shows us that it’s possible to beat this thing. When Bill Gates, one of the few people who did see it coming, was asked on Reddit two days ago about how long the pandemic will last, he responded, “If a country does a good job with testing and shut down then within 6–10 weeks they should see very few cases and be able to open back up.” Places like Taiwan, Vietnam and Singapore show us the way. The last infections have been cleared out of Hubei. And the next time you hear that China did a better job containing COVID-19 because it’s authoritarian, remember South Korea. The issue is competence, not democracy. Trust and transparency motivates people better than coercion.

Don’t let the media superimpose narrative. It’s still too early. Instead, remember Seneca. “We are waves of the same sea, leaves of the same tree, flowers of the same garden.” That’s the only story in the world right now, and we’d all do well to remember it. There are billions of human beings having a similar experience to you in this moment, frustrated teenagers in Turin, grandmothers complaining and cooking meals for their families in Lagos, fathers trying to home school their kids in Mexico City, millions of other office workers trying to figure out how to use the mute button on Zoom. Like you, they’re feeling anxious about their finances, and worried about what the future holds. Eventually though, a year, two years from now, the coronavirus will recede in our consciousness and become a part of history. We’ll rebuild, move on, and try as hard as we can to return to normal.

We shouldn’t.

We can do better.

This time around, let’s not let a good crisis go to waste.

We’re a team of science communicators based in Australia. We curate stories of human progress, and help people understand what’s happening on the frontiers of science and technology. More than 35,000 people subscribe to our free, fortnightly email newsletter. You can also find us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.